The occupiers’ aim was to put these men to work in Germany. After the heavy German losses at Stalingrad, there was an urgent need for manpower to keep the German war industry running. German workers were being drafted into the Wehrmacht, and Nazi Germany therefore sought labor from occupied countries. Dutch citizens who refused to work in Germany faced severe punishment. Outrage spread rapidly across the country—people had had enough.

The first to go on strike were the workers at the Stork machine factory in Hengelo. They called nearby companies and other friendly firms across the country. A crucial role in spreading the strike was played by Femi Efftink, Stork’s telephone operator. On her own initiative, she connected dozens of calls to other factories in Hengelo and surrounding towns, repeating the same message everywhere: “Stork is on strike—will you join us?”

Thanks to her phone calls, the news spread like wildfire across the country. More than 200,000 men and women laid down their work. It became the largest strike in Dutch history and the biggest act of mass resistance in occupied Europe. The Nazis brutally crushed the strike, declaring martial law after just two days (on May 1, 1943). People were executed on the spot—sometimes after only a summary trial.

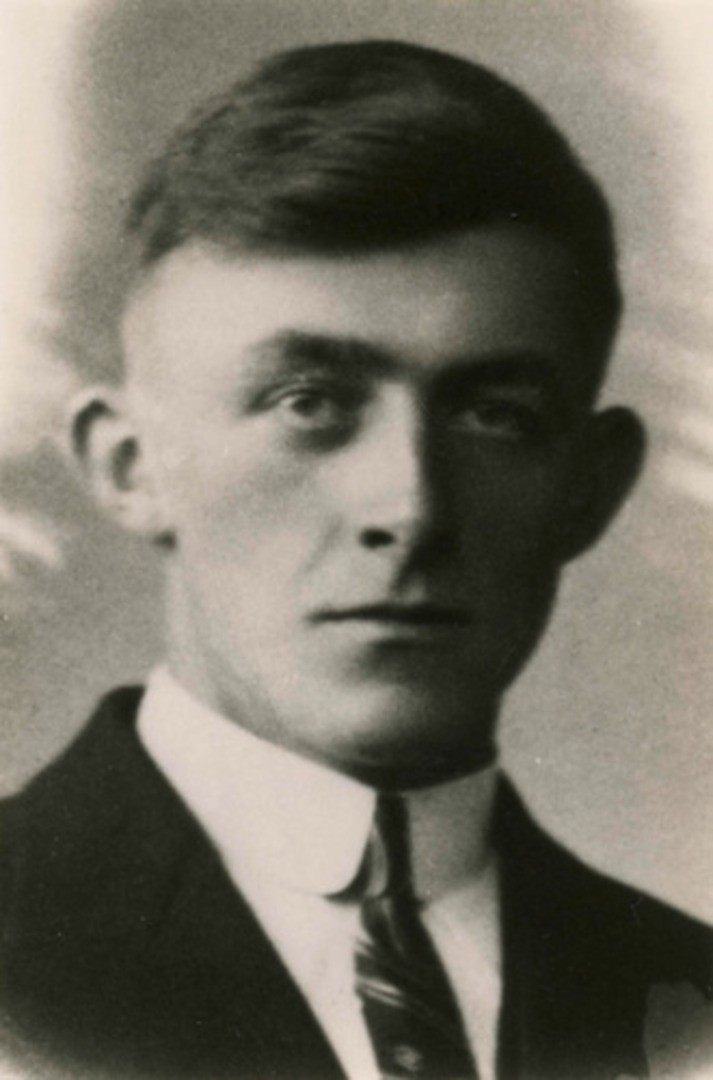

In Friesland, many joined the strike as well, which became known in the north as the “Milk Strike” (Melkstaking). Farmers stopped delivering milk to the dairy factories. One of them was Freerk Wijma, a 44-year-old farmer from Sumar. On May 4, 1943, a patrol of the Ordnungspolizei encountered a farmhand carrying a half-filled can of milk. He was forced to reveal where the milk had come from. It was traced back to Wijma, and the patrol immediately drove to his farm.

The Germans surrounded the property. Wijma tried to escape through a bedroom window but failed. When asked whether he had delivered milk to the factory that morning, he replied that he had not. He was then ordered to come with them to Leeuwarden. The farmer refused. He is said to have replied:

“If I must die, then shoot me here on my own land.”

When Wijma refused a second time, the German commander gave the order to fire. Wijma was shot in the head at close range and died later that afternoon. Freerk Wijma thus became one of the dozens of victims executed under martial law during the strike.

In retrospect, the strike can be seen as a turning point in the occupation period. Whereas in the early years the Dutch population largely endured the occupation passively, the Milk Strike marked a change in attitude. From that moment on, the willingness to join the resistance or to shelter people in hiding grew significantly.